A Novel Incentive Model for Uptake of Diagnostics to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance

Since 1984, the UK’s second Wednesday of each March is NO SMOKING DAY (NSD). The NSD aims to encourage smokers who want to quit. In 2022, NSD falls on the 9th of March and has the slogan “Today is the Day”.

On the occasion of the 2022 NSD, a reflection on where the UK is regarding smoking trends is warranted. A historical OHE publication (1) adds an interesting perspective. It allows us to ponder whether deaths and cases associated with lung cancer, mainly due to smoking, are where we expected them to be back in 1994.

In 2019, about 1.14 billion individuals worldwide were active smokers, and smoking tobacco accounted for approximately 7.69 million deaths and 200 million disability-adjusted life-years. Smoking tobacco was the leading risk factor for death among males, accounting for 20.2% of deaths (2).

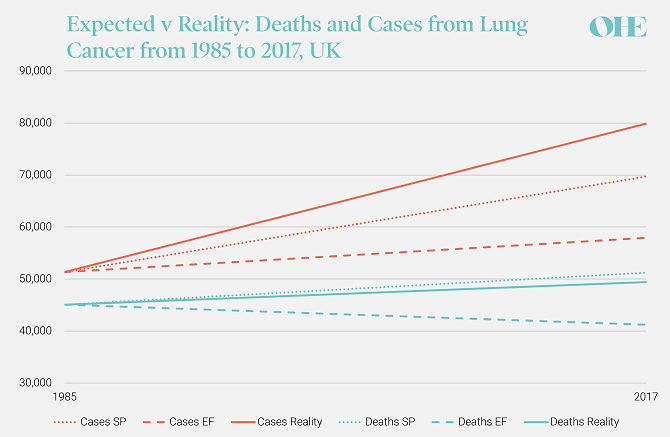

Cigarette smoking explains above 80% of lung cancer deaths (5), and, interestingly, OHE, in 1994, published a study that predicted a significant increase in the number of cases and deaths from lung cancer from 1985 to 2017 based on a simple extrapolation (standard forecast) of 1985 data by the Office of Population Statistics Survey. This prediction relied on the British population growing from 57.8 million to 61.7 million in twenty-five years. Additionally, an adjusted forecast was elicited from a UK expert panel. The standard- and expert-based predicted figures for lung cancer deaths for 2017 in the UK were 69,700 and 57,900, and, for cases, 51,200 and 41,200. Hence, the expert panel shifted the standard forecast downwards by about 17% for deaths and 19% for cases.

Retrospective data gathered by the Global Disease Burden Study (3) shows that the actual number of deaths due to lung cancer in the UK in 2017 was about 49,390, well below the standard and the expert-based predictions. Interestingly, the number of new cases in 2017 was 79,863, which is above the predictions of the expert panel and quite close to the standard prediction. In the meantime, the British population grew by almost four million more than predicted, reaching 65.6 million in 2017.

Source: OHE analysis using CRUK (6) and ONS (7) data. SP: Standard projection. EF: Expert Forecast

Comparing the predictions in OHE (1) and reality spawns several considerations. Firstly, the fact that the actual number of deaths is lower than the standard projection, despite the much larger actual increase in the population (as assumed by the projection), signals that medical treatment for lung cancer has advanced even more than predicted by the experts.

Secondly, the actual prevalence is higher than both forecasts due to the population growth, despite a decrease in the uptake of smoking in the UK (9).

The findings above corroborate the amply documented (3,4) effectiveness of demand-reduction policies in lowering the incidence and prevalence of smoking tobacco even in countries with very diverse income levels. Demand-reduction policies in use since 1990 have ranged from banning cigarette advertisements to cigarette packs containing health warnings, increasing tobacco products excise taxes, and outlawing smoking in public transport and public and private spaces. However, there are still reasons to limit our optimism. Countries with large populations and high prevalence are still experiencing increased deaths attributable to tobacco smoking (i.e., China, Indonesia). Second, nations with intense population growth experience constant or increasing smokers over time (2). These two factors combined explain the still massive burden of disease of smoking tobacco in the world.

Bringing back the focus of the original 1994 OHE briefing, behavioural changes imposed by anti-smoking demand-side interventions worldwide and medical advancement in the detection and treatment of cancer have contributed markedly to ameliorating the burden on smoking on society. However, there is still a way to go.

References

Citation

Hall, M. (1994) The Impact of Behavioural and Biomedical Advance on Health Trends over the Next 25 Years. OHE Briefing.