The Oxford English Dictionary defìnes the skin as ‘the continuous flexible integument forming the usual external covering of any animal body; also the layers of which…

The Oxford English Dictionary defìnes the skin as ‘the continuous flexible integument forming the usual external covering of any animal body; also the layers of which this is composed’. It forms a barrier between the body and its environment. Its impermeable outer layer,…

The Oxford English Dictionary defìnes the skin as ‘the continuous flexible integument forming the usual external covering of any animal body; also the layers of which this is composed’. It forms a barrier between the body and its environment. Its impermeable outer layer, the epidermis, keeps water and other external substances out while conversely it controls loss of water, electrolytes and other substances from within the body. The topmost horny layer of dead cells can also be likened to a desert, an inhospitable environment for invading bacteria, not only because of its dryness, acidity and its lack of life supporting substances but also because it is in a constant process of shedding itself. The epidermis also screens light and absorbs it with the melanin pigment. In addition, the skin hinders the passage of some types of radiation though it does not form a total barrier from any type apart from alpha particles. In man, the hair does not perform the same heat conserving function as it does in furry animals though the remaining hair on the scalp protects against ultraviolet light and minor injury. The hair roots themselves and the skin glands are a source of new epidermal cells to replace the outermost layer as it is constantly worn away.

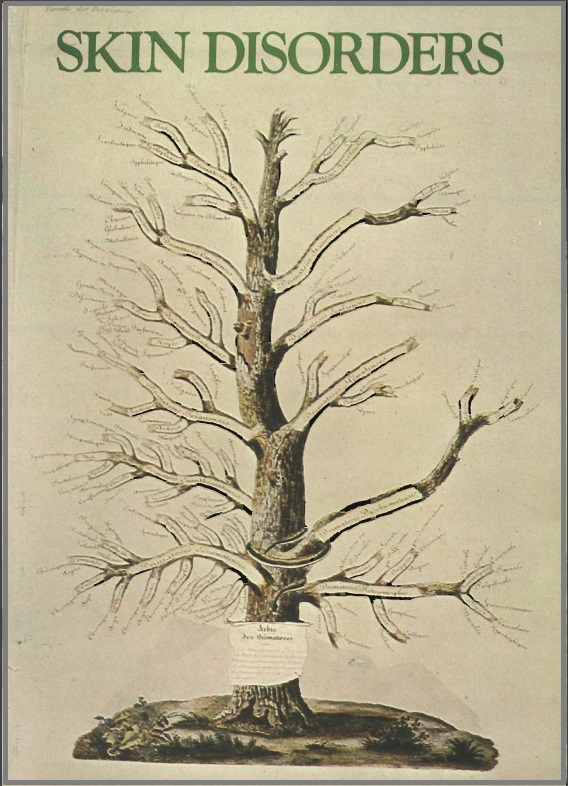

The sort of skin conditions that reach surgeries and clinics in the nineteen seventies are very different to the ‘skin diseases’ which were common before the preventive and therapeutic developments of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In earlier times, when smallpox was endemic, leprosy frequently seen and the skin manifestations of later stages of syphilis common, ‘skin disease’ was associated with these and other grossly disfiguring infectious conditions which led to their sufferers being stigmatised as unclean and dangerous. However, these conditions are rarely seen today and furthermore they are more properly classified as systemic infectious disorders.