As early as 2080 BC reference can be found to epilepsy in the code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon. Special laws affecting the marriage of people…

As early as 2080 BC reference can be found to epilepsy in the code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon. Special laws affecting the marriage of people with epilepsy and the validity of their testimony at court probably reflected unfounded fears and prejudices that…

As early as 2080 BC reference can be found to epilepsy in the code of Hammurabi, King of Babylon. Special laws affecting the marriage of people with epilepsy and the validity of their testimony at court probably reflected unfounded fears and prejudices that have by no means been dispelled by twentieth century enlightenment.

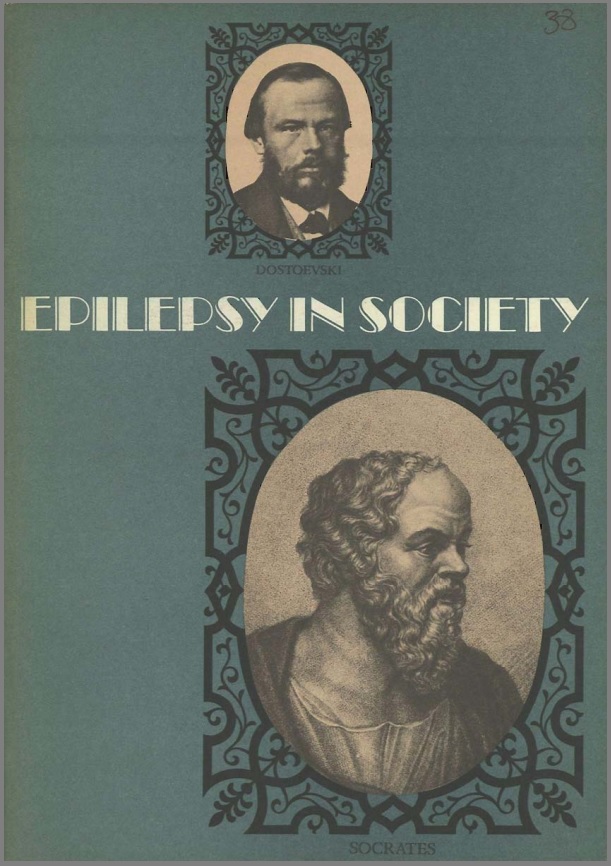

The dramatic and sometimes bizarre manifestations of epilepsy have given it a special place in medical history. From antiquity to the relatively recent past, diseases were seen as phenomena more or less dependent on the supernatural, as divine retribution for wickedness or as products of possession by spirits. Epilepsy more than any other condition was susceptible to explanation in these terms. For this reason the history of epilepsy provides a paradigm for the history of medicine as a whole. Tempkin (1945) wrote, ‘In the struggle between the magic and the scientific conception, the latter has gradually emerged victorious in the western world. But the fight has been long and eventful, and in it epilepsy held one of the key positions’.

During the nineteen thirties the development of the electroencephalograph led to great strides forward in the understanding of epilepsy and the diagnosis of its particular forms. As a tool it has been as basic to epilepsy as X-ray equipment has been to chest disease and the electrocardiogram has been to heart disease. The EEG is invaluable in the differential diagnosis of epilepsy and in locating the site of lesion in the brain, if it is focal. Together with the use of the EEG, surgical techniques have been developed which offer the possibility of successful treatment in some of the cases which do not respond to drug therapy.