Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

A Spotlight on Haemophilia Therapies

In advanced countries, the majority of medical care is no longer concerned with prevention of death. Better social conditions, modern scientific medicine and in particular immunisation and chemotherapy have removed the commonest causes of premature mortality. The remaining deaths before retirement could often…

In advanced countries, the majority of medical care is no longer concerned with prevention of death. Better social conditions, modern scientific medicine and in particular immunisation and chemotherapy have removed the commonest causes of premature mortality. The remaining deaths before retirement could often best be prevented by social measures, such as a reduction in smoking or accidents, and in any case they account for only a small, if dramatic, proportion of medical activity. The health services as such are now most commonly concerned with acute or chronic morbidity, where the objectives are to limit disease or to prevent progressive deterioration.

The extending scope for care can be illustrated not only by the advances in chemotherapy which made possible, for example, the control of infectious diseases, but also by the numerous other advances such as transplants, neurosurgery, radiotherapy, heart surgery and the developments in biochemical analysis and in electronic diagnostic devices. All of these have created in numerable new opportunities for medical or surgical intervention where previously no treatment was possible. It is, however, these advances themselves which have brought in their train the problem in medical care which this paper discusses.

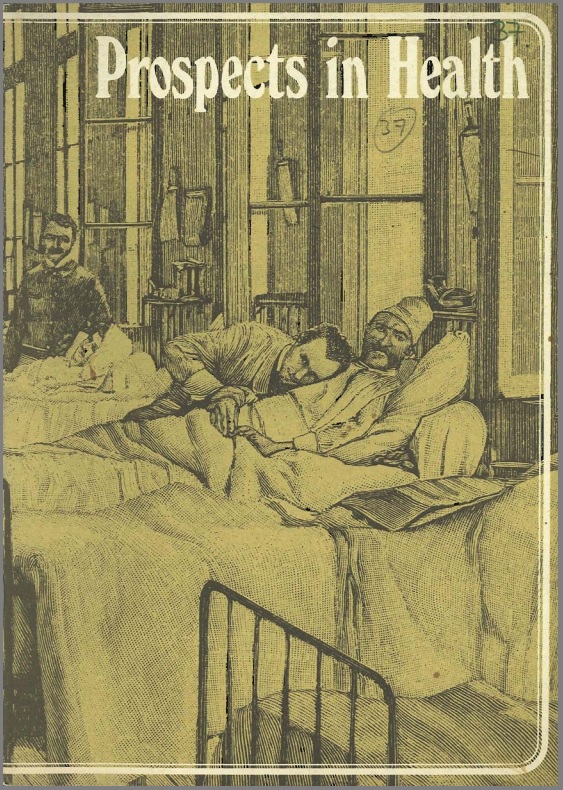

Prospects in Health