Key takeaways

- Providing informal care to someone living with acute leukemia imposes a severe multidimensional burden, reshaping relationships and affecting mental health, physical health, career, finances, social activities and more.

- People who provide informal care (hereafter referred to as carers) must balance their caregiving responsibilities with these other parts of their life. Despite informal care sometimes putting a strain on relationships and other aspects of day-to-day life, carers voiced that they were willing to put the patient first, often to the detriment of their own wellbeing.

- Carers require practical and emotional support, including via health and social care pathways and improved flexibility from employers.

- There is a need for greater consideration of carer burden in health technology assessments to ensure treatments that reduce carer burden are properly valued.

Acute leukemia imposes a heavy toll on both patients and carers

Acute leukemia is a group of aggressive cancers that affect the blood and bone marrow. Acute leukemia progresses rapidly, requires intensive treatment and often leaves patients heavily dependent on family or friends (unpaid, informal carers) for day-to-day support. There is a lack of evidence on how providing care for people with acute leukemia affects these informal carers. Recognising and valuing the burden of informal care is increasingly important for clinical practice, health technology assessment, and the development of interventions, support and care strategies that address both the needs of patients and carers.

We spoke to carers in six countries

To better understand how providing informal care for an adult with acute leukemia affects carers’ quality of life, we spoke to 60 informal carers, 20 from European Union countries – including 5 each from France, Germany, Italy and Spain – and 20 each from the UK and US. We asked them questions about the patient’s diagnosis and how they became a carer, their experience of caregiving as well as questions about their involvement in decision-making and which aspects of treatment they and the person they care for prefer.

Most carers reported a large impact

Over half of the carers who completed a questionnaire measuring the impact of illness on the quality of life of adult family members or partners reported experiencing a very large or extremely large impact.

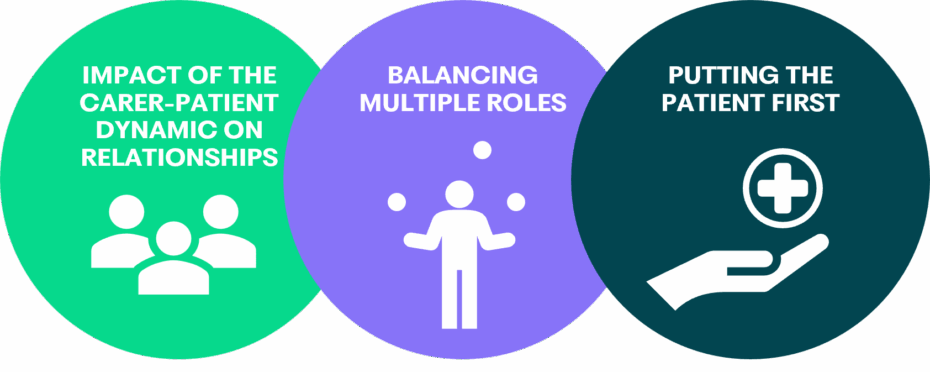

We found three interlinking themes

Impact of the carer-patient dynamic on relationships

Becoming a carer introduces a new dynamic into the relationship between the carer and the person they’re caring for. The journey of experiencing a diagnosis of acute leukemia and subsequent treatment can build resiliency and form stronger emotional bonds and intimacy. This was echoed in the process of facing an uncertain future together when starting treatment phases and living in the shadow of potential relapses.

Balancing multiple roles

One of the most prominent themes was the complexities of balancing existing responsibilities with the additional demands of caregiving. Carers often reported making professional and financial accommodations, such as requesting more flexibility, reducing working hours or taking a career break to enable them to devote enough time to their loved ones. Caregiving responsibilities were constant and wide-ranging, including housework, emotional support, assisting in treatment adherence, providing transport to medical appointments and performing administrative tasks. These additional tasks often meant that carers experienced role conflict, such as struggling to maintain the boundaries between their relationships to the person they care for or deprioritising other aspects of their lives and relationships, due to competing demands on their time.

Putting the patient first

Another recurrent theme was putting the patient’s needs above their own. The often-intense responsibilities and mental toll of caregiving can have a negative impact on a carer’s own quality of life. Personal health, leisure activities and social interactions were frequently deprioritised. Understanding medical information about treatment options and considering decisions about their loved one’s future was mentioned by some as a burden in itself. Despite the considerable and wide-ranging impact, many carers expressed that they are willing to prioritise the patient regardless of the burden on themselves.

Policy Implications

Our results demonstrate that informal caregiving imposes pressures that accumulate into a substantial, multidimensional burden. It is essential to ensure carers receive appropriate support, and that healthcare professionals and decision-makers recognize this burden.

Including carers in the clinical pathway

Improving access to targeted support could help improve carer quality of life. Practical steps could include mental health screening for carers in acute leukemia clinics and hematology wards and clear referrals to counselling, respite, and financial advice, timed to key stress points such as at diagnosis, onset of treatment, and hospital discharge. This could help to ease the strains of role conflict and prevent avoidable physical and mental health declines in carers.

Flexible workplace policy

To allow carers who are still working to continue to work while managing their caregiving responsibilities, employers should ensure that workplace policy aligns with what carers value most in their work environment, including accommodations such as remote working, flexible and adjustable hours, as well as formal carer leave policies.

Recognising carers in treatment development

Therapies that shorten hospital stays, simplify dosing, or reduce toxicity can ease carers’ anxiety, improve sleep, and preserve daily routines and employment. Considering the perspectives and experiences of carers can help to ensure that, in the future, treatments and strategies developed in acute leukemia can benefit both patients and carers alike.

This research paper was commissioned and funded by the Acute Leukemia Advocates Network (ALAN) who also conceived the initial idea for this study.