Unlocking the Value of Combination Therapies

Previous studies concerned with the benefits of modern medicines have concentrated mainly on their economic consequences (Wells NEJ 1980; Teeling-Smith G 1982).

By contrast this paper discusses the more difficult problem of evaluating the contribution of medicines to the quality of life. It…

Previous studies concerned with the benefits of modern medicines have concentrated mainly on their economic consequences (Wells NEJ 1980; Teeling-Smith G 1982).

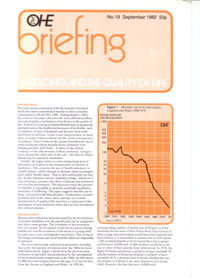

By contrast this paper discusses the more difficult problem of evaluating the contribution of medicines to the quality of life. It starts by looking at familiar British data on premature mortality and at the traditional measures of morbidity, such as numbers of days in hospitals and absence from work attributed to sickness. It puts a new interpretation on these data, in terms of bereavement and the social consequences of sickness. Next it looks at the extent of world-wide use of some medicines whose benefits derive primarily from making patients ‘feel better’. It refers to the clinical evidence of the effectiveness of these medicines, and goes on to discuss the other side of the coin – the adverse effects which may be caused by medicines.

Finally, the paper turns to a new and growing area of discussion in relation to the measurement of benefits of medicines. This concerns the use of ‘health indicators’ or ‘health indices’ which attempt to measure what sociologists have called ‘health status’. That is, how well people feel they are. It also discusses various ‘disability ratings’, which are a way of trying to measure the effects of disease and treatment on everyday performance. This discussion raises the question of whether it is possible to quantify essentially qualitative measures of wellbeing. The paper suggests that this can be done, at least for individual diseases. Furthermore, it seems probable that in the future these attempts at a formal measurement of quality of life may form a routine part of the assessment of new medicines when they are first introduced into clinical practice.

Medicines and the Quality of Life

Teeling Smith, G.

(1982) Medicines and the Quality of Life. OHE Briefing. Available from https://www.ohe.org/publications/medicines-and-quality-life/