OHE invited Climate Change Economist, Professor Elizabeth Robinson to give the 2023 Lecture at the Royal Society of Medicine. She used the opportunity to demonstrate the importance of a one health perspective when transitioning into a climate-resilient future.

As part of OHE’s charitable purpose to educate and inform health policymakers and the public, the OHE Annual Lecture is an opportunity to highlight urgent and important issues facing health systems around the world and to raise awareness of research and evidence that can contribute to addressing these challenges.

Throughout 2023, the sustainability of health and health care has been a major area of research for OHE. Given the importance and scale of the problem climate change poses, it will remain a core research agenda going forward, with sustainability being one of two main areas of focus for OHE’s new Change Initiative.

Professor Robinson is Director of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics & Political Science. Her lecture reframed the economics of health and healthcare in a changing climate, outlining how having a healthier environment, livelihood and life can contribute to climate change mitigation and resilience.

THE ECONOMICS OF HEALTH IN A SHIFTING CLIMATE: FOSTERING WELL-BEING, SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS AND A GREENER FUTURE

The climate crisis impacts all of us, and we all have a part to play in addressing it. To give some rather harrowing perspective on the extent of damage caused by healthcare emissions, if healthcare were a country, it would be the fifth largest carbon emitter in the world. There are two major challenges to tackle:

- the impact of health care on the planet

- the impact of the climate crisis on our health

The involvement of health economics is integral in grasping the interplay between climate and health to ascertain how health care markets can transition towards sustainability.

Identifying the gaps

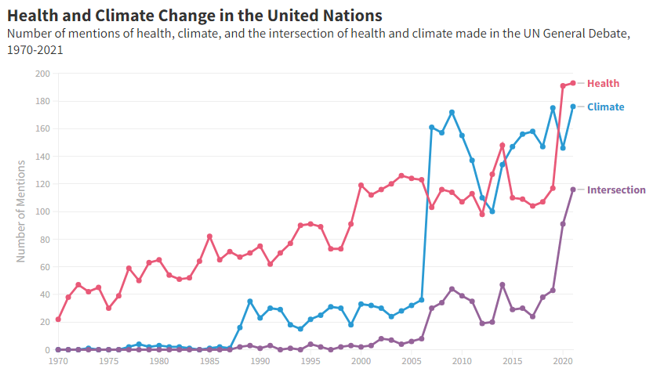

Professor Robinson began the lecture by exploring how frequently the terms “health” and “climate change” were mentioned individually and simultaneously in UN general debates between 1970 and 2020. It was evident that over the last decade, the intersection of health and climate change has more than doubled, indicating global political interest in the topic.

When comparing which academic journals were engaging with the same terms, it is alarmingly clear that whilst these topics are frequently explored by environmental economists, there is comparatively less attention in mainstream economics journals and health journals. This illustrates a real gap in interest and knowledge within the health economics community.

THE LANCET COUNTDOWN

Professor Robinson shared key insights from the important work she is contributing to at the Lancet Countdown as Working Group One Lead. Through their annually updated monitoring system, the Lancet Countdown indicators allow tracking and analysis of the links between climate hazards, exposures, and vulnerabilities through to outcomes. This data brings clarity to the complex interactions between health and climate change to provide an understanding of how various risk factors (e.g., age) combined with hazards (e.g., heatwaves) relate to negative health repercussions.

One staggering example of the powerful insights the Lancet Countdown is providing policymakers and researchers is that a 1% temperature increase results in approximately 30 million additional food-insecure people. This is the case even after controlling for other confounding factors, such as urbanisation. This powerful tool is offering us data that directly presents the worsening of food insecurity due to climate change alone.

Vulnerability

Professor Robinson reminds us that whilst climate change is a huge factor, there are a myriad of socio-economic challenges at play too, and that climate change may act as an interaction or multiplier effect.

Using an analogy of climbing an escalator, she demonstrated why climate change makes staying healthy and providing healthcare more challenging. If someone is walking up an initially stationary escalator, and it starts moving down slowly, it is still possible to make progress climbing upwards, just at a slower pace. This idea can be seen to encapsulate what climate change is doing to our efforts to improve health outcomes. However, if we consider a person who is less able to walk up the stairs at the same pace, because they are older, or have a pre-existing health condition, they may not be able to walk up fast enough to counter the downwards movement, highlighting their vulnerability. This is why in many countries with additional socioeconomic burdens, the impact of climate change can outweigh efforts being made towards sustainable development; thereby negating health gains that would be easier in a country with a less vulnerable population.

There is no doubt that the Lancet Countdown is facilitating a real depth of understanding of how climate change is impacting health. But what can we do with this information? Of course, when projecting this data into the future, it opens the possibility of identifying vulnerability ‘hotspots’ across the globe where there are already food insecure people.

ONE-HEALTH APPROACH

There is now more evidence than ever before of the negative repercussions of climate change across sectors, all influencing health in various ways. Professor Robinson stressed the importance of thinking about the broader environment that we live in when we are trying to improve healthcare and provide healthier livelihoods. Taking this holistic approach is integral to building effective resilience outside of the realms of the traditional healthcare arena.

Notable examples of health determining sectors include:

- Energy

- Transport

- Building

- Agriculture

- Urban

The diversity in this list underlines the need for cross-sector collaboration and investment to better understand the ‘health economic / climate co-benefits nexus’. This synthesis will enhance our ability to improve the current state of our health systems to be prepared for combatting these issues.

TRANSLATING THIS INTO ACTION: POLICY

Learning how we can turn this crisis into a pragmatic plan moving forward is key to alleviating the detrimental impacts of climate change and attaining resilience. Of course, it is a no brainer that we need policymakers at the forefront to catalyse the necessary policy changes at a local, national and global level.

One of the most compelling quotes shared from the Lancet report states that “tackling climate change could be the greatest global health opportunity of the 21st century”. This reaffirms the imminent necessity for policymakers to engage with the evidence pragmatically.

The lecture provoked many questions from the audience revolving around the role of politics and policy change, shared during the Q&A session. When asked what changes were occurring to incorporate health in the grander scheme of our political lives, Professor Robinson was transparent about her disappointment in the government for not implementing what she refers to as ‘the great reset’ that was expected in a post-covid context. This failure to prioritise health and healthier environments, and continually making investment in renewable energy more difficult highlights some necessary next steps for change.

When asked more specifically about policy prescriptions, Professor Robinson gave some examples of regulation that could be efficacious, including implementing free transport for children as a way to reduce air pollution. Importantly though, she observes that when a country has a lot of inequality, the power of policy prescriptions is weakened. As such, explicit regulatory policies are not the only effective method of provoking change. Strong nudges from public campaigns and price subsidises can be a great way to encourage people to make the relevant changes.

IT’S NOT ALL DOOM AND GLOOM

A question was raised regarding the concrete actions being taken by the healthcare sector to address the extent of the pollution.

Professor Robinson discussed the work the NHS are currently undertaking to support the innovation and implementation of clinically equivalent, low carbon asthma inhalers. This is predicted to reduce carbon emissions by 374kt by 2040 (Delivering a Net Zero Report, NHS) So, whilst there is certainly significant work to be done, it is clear that the mobilisation of sustainable long-term planning within the NHS is occurring and that noise centring on the green dividend is being made.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Professor Robinson reminded us that the leading causes of ill health are “increasingly beyond the control of the traditional reach of the healthcare sector”. What she alludes to here is the persistent reliance on the healthcare sector as a ‘curative’ solution for poor health. Contrarily, focusing on the varying preventative measures we can take to tackle the admonitory precursors of ill health is of great value. This is why there is a true urgency to:

- create healthier living environments

- invest in the health determining sectors

There is a growing body of compelling research evidencing the health co-benefits of climate mitigation. For example, adopting low-carbon, plant-based diets can reduce agricultural emissions whilst simultaneously reducing dietary risk factors from non-communicable diseases. Utilising the existing evidence to engage people to “improve health, reduce pressure on health services and contribute to tackling climate change” can be the fundamental stepping stones for the right people to cultivate a pathway towards a greener future.

Professor Robinson concluded by noting the insufficient focus on the wide range of cost and benefits of implementing these changes. Finally, leaving the audience to reflect on the palpable value of environmental and health economics collaborating to accelerate the transition to net zero and towards healthier lives.