Unlocking the Value of Combination Therapies

Since the Office of Health Economics (OHE) published a critique of CBO’s new simulation model of new drug development late last year, the U.S. public sector think tank has made three improvements to its methodology. We review these updates, assess…

Since the Office of Health Economics (OHE) published a critique of CBO’s new simulation model of new drug development late last year, the U.S. public sector think tank has made three improvements to its methodology. We review these updates, assess their impact, and highlight the key remaining limitations of the modelling approach, concluding that policymakers should still exercise considerable caution in relying on its predictions.

Snapshot

The Senate may soon turn back to reviving pieces of the Build Back Better Act (BBB) which passed the House at the end of last year but failed to reach a vote on the Senate floor. While much of the bill remains controversial, it includes provisions directly related to one issue for which interest does not wane in Washington: drug pricing policy.

The drug pricing provisions of the BBB called for government price setting for certain top-selling drugs, as well as penalties for biopharmaceutical companies who increase prices faster than inflation. While the true implications of imposing price regulation for prescription drugs are unknown, experts agree that it could have wide-reaching long-term effects on the future of innovation.

To aid policymakers in understanding the potential impacts of drug pricing policy on future innovation, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has developed a model that simulates decisions about research and development (R&D) investments to quantify the reduction in the number of new drugs expected to reach the U.S. market. But modelling the effects of pricing regulations on incentives to invest in R&D and the risks in drug development is a challenging task. Peer-reviewed literature documenting the relationship between industry revenues and drug development is limited and outdated. And the R&D ecosystem has evolved considerably in the last several years, relying more on small start-ups backed by venture capital investors than the classic large pharmaceutical companies.

Late last year, the Office of Health Economics (OHE) published a critical evaluation of CBO’s simulation model. We concluded that the model’s assumptions about investment in new drug development were unrealistic and that CBO would underestimate the true losses in drug innovation that would occur if the government were to set prices for prescription drugs. Because the estimates produced by the model were limited and uncertain, we urged policymakers to exercise caution in relying solely on CBO’s findings to evaluate the impact of real-world policy changes.

Since then, CBO has made three technical improvements to its simulation methodology. We review these updates, assess their impact, and highlight the key remaining limitations of CBO’s modelling approach. A more detailed treatment of these limitations is provided in an updated version of the report originally published last year.

CBO’s simulation approach to modelling pharmaceutical R&D investment decisions

Analysis by OHE and others has identified several challenges with CBO’s initial approach to estimating the impact of drug pricing reform on pharmaceutical innovation, which relied on historical estimates from the literature to predict the industry-wide relationship between revenues and new drug development. These estimates came from older empirical research with arguably limited relevance to a government price-setting policy of the size and magnitude being considered by Congress.

In August 2021, CBO released a working paper describing an alternative methodology – a general simulation model that can be used to evaluate any policy which alters expected pharmaceutical industry returns (e.g., any policy reducing drug prices) or R&D costs. This approach attempts to model the investment decision-making process of a hypothetical pharmaceutical company from the “bottom-up” to simulate the relationship between expected net revenues and new drug development.

To illustrate the workings of their simulation model, CBO evaluated a hypothetical sample policy that would reduce expected industry revenues by 15-25% for products in the top 25% of drugs ranked by expected returns. The model is used to estimate the impact of this sample policy on the probabilities of a drug candidate moving into each phase of clinical development and ultimately on the number of new drugs approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA).

Three updates to the model

In a presentation to the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Climate Practice on January 13, 2022, CBO described three technical improvements to their simulation model:

As a result of these revisions, CBO now estimates that their hypothetical sample policy would decrease the number of new drugs coming to market by 10% in the long run. This is two percentage points higher than their initial estimate of 8% and the difference is equivalent to one fewer drug per year assuming CBO’s time-constant baseline of 44 new drugs entering the market each year in the absence of the policy. Thus, these technical improvements represent a 25% greater estimated loss in new drug development associated with the modelled price regulation, which highlights the high degree of uncertainty in this simplified model and illustrates that adjustments can have a meaningful impact on the results.

While the technical improvements to the model – including the accounting for effects on preclinical development, which was discussed in detail in OHE’s original critique – are welcome, significant limitations remain. As a result of these limitations, CBO’s model will continue to underestimate the true innovation losses that would likely occur under a government price-setting policy.

At least three key limitations remain:

1. CBO assumes that pharmaceutical companies make drug development decisions based on an oversimplified decision rule

In CBO’s modelling, a drug candidate will advance to the next phase of development as long as expected returns exceed expected costs for that individual drug. This means that the level of expected net returns does not influence the probability of the drug being progressed, conditional on the returns being positive. The policy could lower expected net returns to almost zero but as long as they remain above zero, it will have no impact on the probability of the drug being progressed into the next stage of development.

In reality, drug developers often require returns to be some positive multiple of costs to recoup the costs of potentially successful and failed investments, suggesting that CBO underestimates the impact of the policy on development decisions. For example, in CBO’s model, two drugs with expected net returns of 0.01% and 15% are equally likely to advance into the next stage of clinical development. Yet, a positive return of 0.1% is hardly attractive for investment when the stock market is earning 7% or when a new green energy investment could garner a 10% return.

Also, pharmaceutical companies often make development decisions about individual drugs with their entire drug development portfolio in mind, a further criticism of the simple decision rule used in the modelling.

2. CBO assumes, unrealistically, that the number of drugs coming to market without the policy would be constant over time

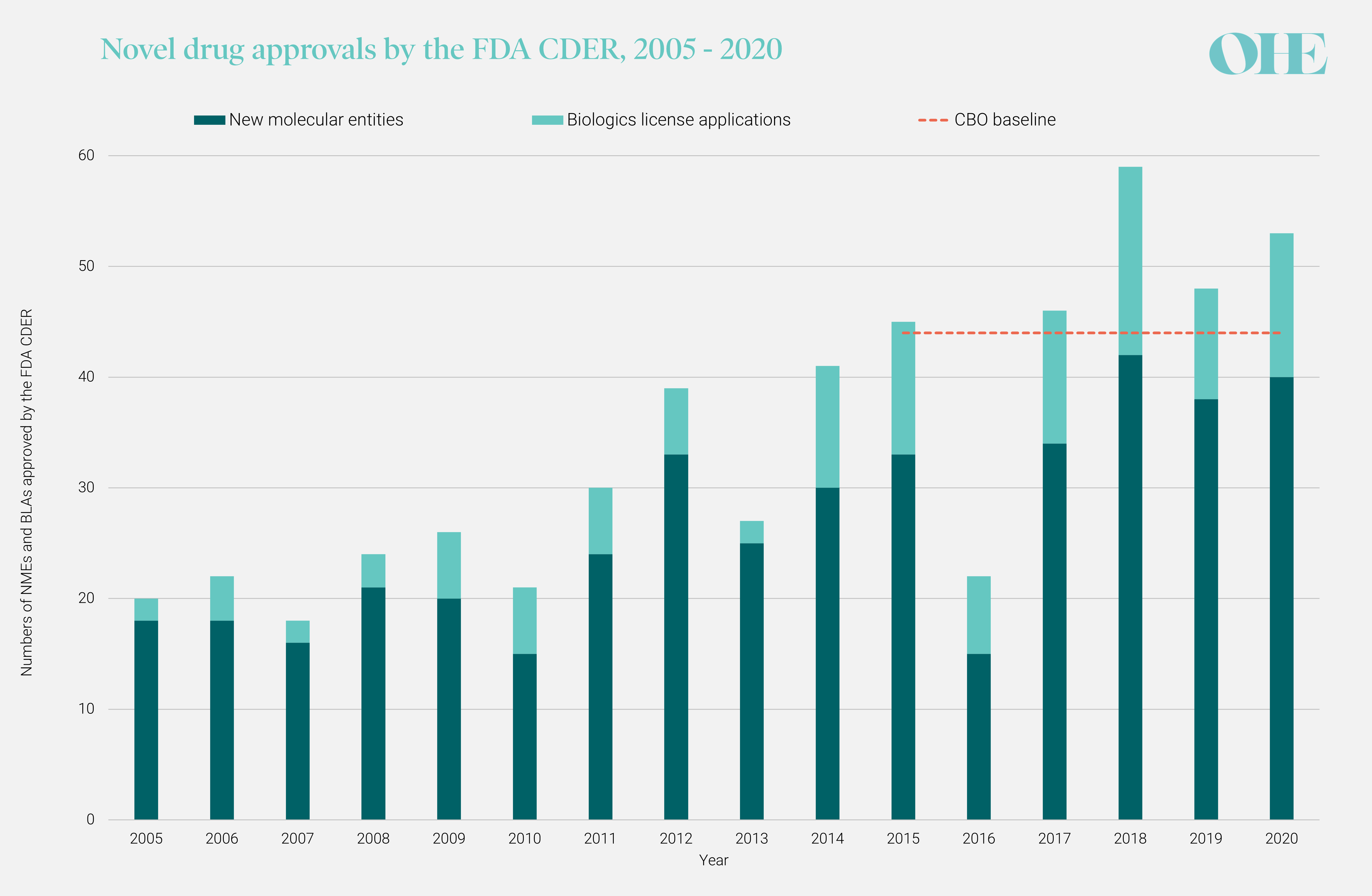

CBO measures the impact of drug pricing policies on innovation by the change in the number of new drugs coming to the market each year and assumes that this number would stay constant over time in the absence of the policy. However, as figure 1 shows, there has been an upward trend in annual Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) approvals since at least 2005, and experts interviewed by OHE have suggested that developments such as genomics will contribute to an increasing rate of new molecular entity (NME) approvals. The time-constant baseline that CBO assumes is 44 new drugs per year, set equal to the average number of annual CDER approvals in the period 2015-19 and represented by the red dashed line in figure 1. While this average includes new biologics license application (BLA) approvals by the CDER, it does not include approvals by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) for products such as vaccines and gene therapies.

It is critical that CBO’s assumed baseline reflects reality. If new drug approvals are expected to increase over time in the absence of the policy as the evidence suggests, then erroneously assuming a constant baseline will underestimate the absolute numbers of medicines being lost to a policy such as the one modelled by CBO. A 10% drop from the 2011 level of 30 CDER approvals is equivalent to 3 drugs, but a 10% drop from the 2018 level of 59 is almost double that.

FIGURE 1: ANNUAL NUMBERS OF NMES AND BLAS APPROVED BY FDA’S CDER

Source: https://media.nature.com/original/magazine-assets/d41573-021-00002-0/d41573-021-00002-0.pdf

3. CBO relies on a narrow conception of biopharmaceutical innovation

The CBO analysis gives an incomplete picture of the losses in biopharmaceutical innovation that would occur under a policy that impacts expected revenues. The only measure of innovation that CBO considers is the number of new drugs coming to market. While this is a natural starting point, drugs do not all have the same health impact. A new curative therapy for a rare disease such as spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) may provide enormous health gains for each patient while another equally innovative treatment may help a much larger number of patients by preventing unnecessary heart attacks and hospital stays.

Estimates of the impact of legislative proposals on human health through declines in biopharmaceutical R&D must be part of a complete evaluation of any policy. CBO explicitly notes that it is beyond the scope of their analysis to consider which types of drugs might be affected by a policy change and how the reduction in new drugs will affect health outcomes. However, without even any analysis of the types of drugs that are likely to be lost, it is impossible to say which groups of patients stand to lose the most.

In addition to these criticisms, the CBO model does not account for the fact that pharmaceutical companies differ in characteristics such as size and development costs, which are relevant for R&D decision-making. Also, the headline estimates are only averages and mask significant uncertainty – around both the values of key inputs used in the model (which were calibrated or estimated) and around the impact of the policy. For example, we find that even small differences in key inputs, such as success rates in early clinical development, can have relatively large downstream effects and therefore meaningfully impact the number of new drugs coming to market (Cookson and Hitch, 2022). Policymakers should exercise caution in relying on CBO’s headline point estimates, given the amount of uncertainty in their estimation.

In summary

CBO’s latest technical improvements to its simulation model are welcome and move the estimated innovation impact in the right direction. However, the model still suffers from serious limitations including an oversimplified decision rule regarding pharmaceutical companies’ R&D investment, a narrow conception of the value of biopharmaceutical innovation, and significant uncertainty in the distribution of the estimated impacts.

Failure to recognize the limitations and caveats in a simplified model of the complex R&D ecosystem can have unintended consequences. Therefore, while CBO’s modelling exercise has academic merit, policymakers should clearly understand that CBO’s estimates are subject to considerable uncertainty and should exercise caution in relying on these findings for evaluating the potential impact of real-world policy changes.

While the short-term savings from government price-setting policies may be attractive, they will come at the cost of significant losses in biopharmaceutical innovation and hence health for the U.S. and global populations over the coming decades. Understanding the impact of a policy that has the potential to significantly reduce the rate of biopharmaceutical innovation – which has played a pivotal role in the development of novel vaccines and treatments during the COVID-19 pandemic – is critical.

Citation

Cookson, G. and Hitch, J. (2021) Limitations of CBO’s Simulation Model of New Drug Development as a Tool for Policymakers. OHE Consulting Report. Available at: https://www.ohe.org/publications/limitations-cbo%E2%80%99s-simulation.

Related Research

Hitch, J., Firth, I., Hampson, G., Jofre-Bonet, M., Garau, M., Garrison, L. and Cookson, G. (2021) The Lower Drug Costs Now Act and Pharmaceutical Innovation. OHE Consulting Report. Available from https://www.ohe.org/publications/lower-drug-costs-now-act-and-pharmaceutical-innovation.

An error has occurred, please try again later.

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

This website uses Google Analytics to collect anonymous information such as the number of visitors to the site, and the most popular pages.

Keeping this cookie enabled helps us to improve our website.

Please enable Strictly Necessary Cookies first so that we can save your preferences!