Sign up to our newsletter Subscribe

Altering the Trajectory of HIV in Europe

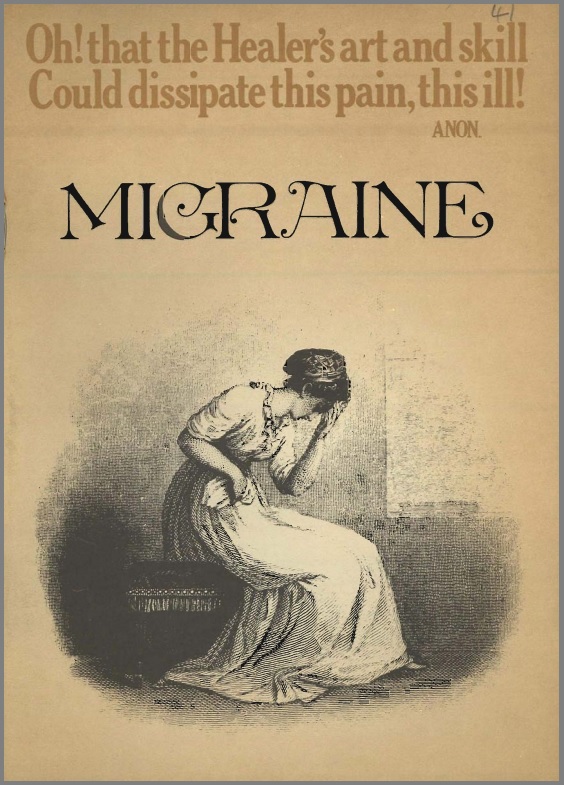

Migraine is typical of the sort of ill-defined self-limiting condition which takes up much of the time of general practitioners. It involves no risk of mortality but it can cause acute intermittent incapacity to the sufferer, occurring with little warning and at times…

Migraine is typical of the sort of ill-defined self-limiting condition which takes up much of the time of general practitioners. It involves no risk of mortality but it can cause acute intermittent incapacity to the sufferer, occurring with little warning and at times which may be inconvenient, socially embarrassing and often costly. Perhaps its nature can be best illustrated by a quotation from Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll, himself a migraine sufferer, ‘ I ‘m very brave really’, he went on in a low voice, ‘only today I happen to have a headache’ (Tweedledum).

Migraine is a condition for which there are no signs which can be objectively measured and doctors must rely solely on a subjective description of symptoms by the patient in order to make a diagnosis. The clinical definition of migraine has been a subject of dispute for many centuries and remains so today. The one symptom that is common to every person with migraine is the recurrence of headache. However, recurrent headaches are rarely the only symptoms of migraine attacks. They are often preceded by warning signs or aurae which may vary from patient to patient and from attack to attack. They are usually accompanied by some transient phenomena such as visual, sensory or speech disturbances. They are often, but not always, concluded by a spasm of nausea or vomiting. Nevertheless, it is often difficult to differentiate between migraine and other headaches. There is no clear-cut line whereby a headache can be diagnosed as migrainous or not.

Migraine may be divided into two main sub-groups. First, classical migraine, where the headache is preceded or accompanied by visual aurae, sensory or speech disturbances and second, non-classical or common migraine which is not associated with this sort of sharply defined focal neurological disturbance. In both these types the headache is unilateral and may be associated with nausea or vomiting. Common migraine is by far the more prevalent of the two. Other symptoms may include feelings of elation or depression without apparent cause during the twenty-four hours preceding the attacks, total loss of appetite and, especially among women prone to premenstrual tension, a tight feeling affecting the skin. Large quantities of urine may be excreted as the attack is waning. Patients may also experience neurological symptoms such as numbness, ‘pins and needles’ or giddiness. Table i shows a list of warning symptoms that may precede an attack.

Other less common types may occur. Among these is the cluster headache which is characterised by intense unilateral pain involving the eye and one side of the head, associated with symptoms of flushing, nasal congestion and watering eyes. These attacks usually recur once or more a day lasting for 20-120 minutes in bouts which commonly continue for weeks or months but are separated by remissions of months or years. The condition is distinguished from other types of migraine by the absence of warning signs and by the presence of unilateral flushing.

Facial migraine is another variant. As its name suggests, its main features are those of unilateral episodic facial pain associated with the symptoms of either migraine or cluster headache. Two rare forms are ophthalmoplegic migraine and hemiplegic migraine. The former is associated with the occurrence of prolonged double vision and the second with the temporary paralysis of one side of the body.

Because migraine is so little understood, it is perhaps not surprising that myths have grown up about the incidence of the condition and the characteristics of sufferers. There are strong beliefs that migraine is a neurotic disorder. A typical migraine sufferer is generally thought to be highly intelligent, highly strung and a perfectionist. It is also commonly believed to be an hysterical female disorder and it is often thought to occur more frequently among men and women whose occupations involve concentrated work using the eyes. None of these beliefs, however, is supported by hard evidence.

Migraine