In this year’s Annual Lecture, Prof Anita Charlesworth takes a closer look at the NHS 10 Year Health Plan, concluding that all is not lost for the NHS, but questions of coherence, capacity, and capability remain.

One of OHE’s charitable objectives is a commitment to educate and inform the public and policymakers about the most urgent issues in the healthcare sector. OHE’s Annual Lecture is an opportunity to highlight critical health challenges around the world, and to amplify the research and evidence that can inform how we address these questions.

Three years ago, to commemorate OHE’s 60th anniversary, we launched the Change Initiative – a multi-stakeholder international forum that brings together representatives from governments, industry, non-profits, academia and spokespeople from patient groups, civil society and much more, to leverage their collective expertise and perspectives.

Collaborating with these partners, we help tackle the challenges, delivering insights that shape smarter policies, foster innovation, and improve health every day.

One area of focus for the Change Initiative is prevention, acknowledging that a shift a reactive, treatment-focused society to a proactive and wellness-based one will have a transformative impact not just individually but at a wider socioeconomic level.

Prevention is also at the heart of the UK NHS 10 Year Health Plan, which is a welcome step towards recovering a free, accessible, working health service. The 10 Year Plan’s holistic approach to health is to be commended. Community-based health services will include debt advice, employment support and weight management: recognising that health doesn’t exist in a silo, and nor should healthcare.

But the underlying question however is how this will all be funded. Much of OHE’s commentary on the 10 Year Plan focused on the ‘how’ and ‘who’ of prevention funding. Ahead of the Plan’s publication, our comment piece in the Financial Times argued that we need a new consensus on prevention with the government elevating health above short term political cycles, and investing in non-health factors like air pollution or housing standards.

After the Plan was announced, we put forward proposals for new financing models – both within and outside NHS budgets – with a commentary in Public Sector Focus.

We also highlighted the importance of increasing vaccine uptake in a Letter to the Editor in the Guardian. Simon Brassel, a Senior Principal Economist at OHE wrote in response to the rise in measles cases in the UK, proposing that we need to expand where vaccines are administered – meeting people where they are, and suggesting that the 10 Year Plan’s health visitor model is a good example of this.

Our ongoing work with the Change Initiative will also advance our research into prevention, with a particular focus on how to fund it.

The Plan demonstrates the government’s commitment to invest in its recovery – but how viable is it, and where do we go from here?

The 2025 OHE Annual Lecture, delivered by Professor Anita Charlesworth, focused on the main implications of the plan, and where its limitations lie.

Professor Charlesworth began her address by asking what it means to ‘turn the NHS back around’. She set out the WHO’s health system objectives – which are expectations of affordability, accessibility, sustainability, and high quality – and demonstrated how the UK is struggling on nearly all of these metrics.

NHS performance: health outcomes, productivity, and public satisfaction

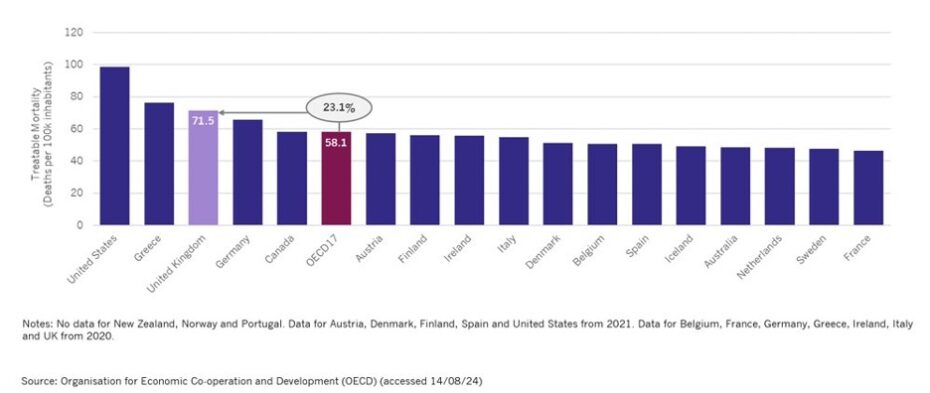

The UK is seeing healthy life expectancy fall below the retirement age: a development with profoundly concerning implications for an aging population. Additionally, the UK has a comparatively high rate of mortality from treatable causes, performing a full 23% higher than the average of its OECD peers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The UK has a comparatively high rate of mortality from treatable causes

Professor Charlesworth also stated that public satisfaction with the NHS has fallen to its lowest level since records began in 1983. Access targets, as laid out in Lord Darzi’s report, haven’t been met for roughly a decade and tell a similar story. Meanwhile, productivity — which outperformed the wider economy before the pandemic — has taken a significant hit, falling approximately 9% below pre-pandemic levels.

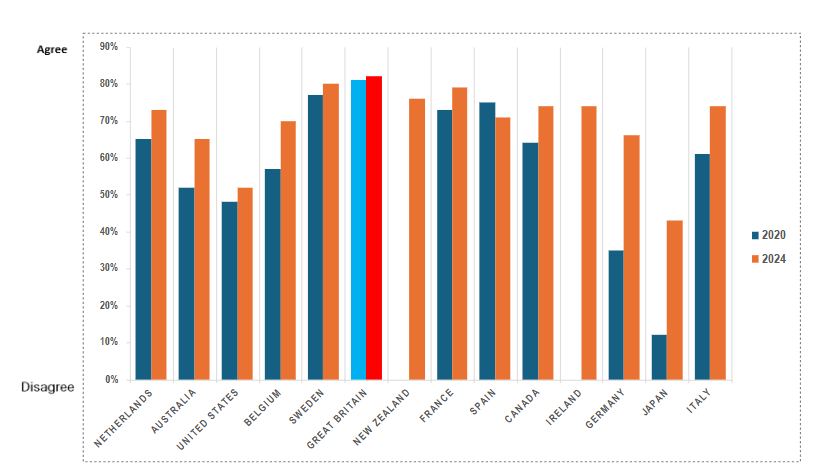

However, Professor Charlesworth pointed out that it isn’t just the NHS that is struggling across the WHO’s metrics for a performing health system. International data from Ipsos Mori surveys show declining satisfaction with healthcare quality across most high-income countries, with the exception of Japan (Figure 2). However, the UK ranked highest for public perception that the health system is overstretched.

The challenge then, Professor Charlesworth stated, is for the NHS to both recover from the strain of the COVID-19 pandemic and to also begin to put in place a system that’s better able to deal with its underlying pressures.

Figure 2: Public perceptions on how overstretched the health system is (Source: Ipsos Health Service Report)

Financing the NHS

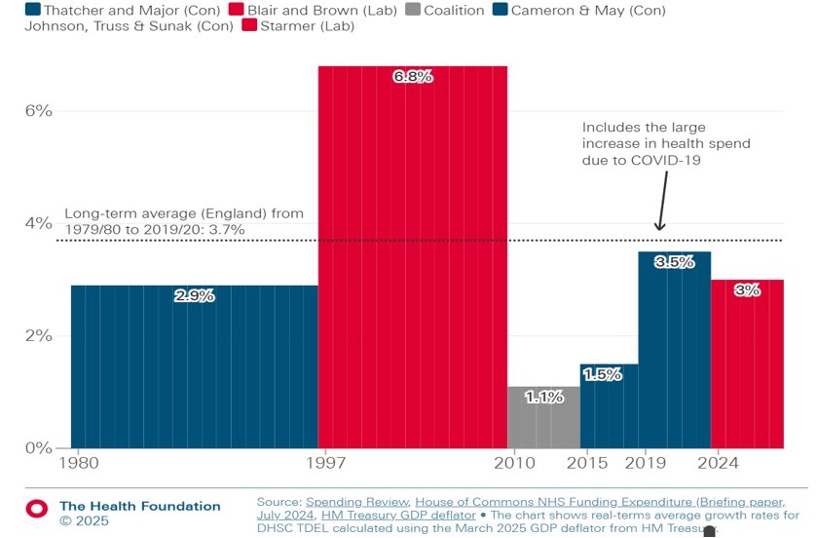

Professor Charlesworth stated that the current Labour government has set out plans to increase health spending by 3% above inflation – for context, this is much less than the previous Blair and Brown administrations, and more than the decade of austerity, but still below the historic average of healthcare spending (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Average real-terms growth in total health spending by government

This spending will be financed, as it typically has been, by shifting resources from other areas into the healthcare sector. However, Professor Charlesworth warned that this isn’t a sustainable long-term strategy as many other public services play an important role in the wider determinants of health. There are also competing demands by other sectors, such as defence, which are now receiving wider political commitments.

Professor Charlesworth then invoked Stein’s Law: “If something can’t go on forever, it will stop”. Tax as a share of GDP is now higher than at any point in the postwar period. Clearly, these traditional levers for funding the NHS are approaching, if not already at, their limits.

A focus on prevention

The NHS 10 Year Plan articulates three key shifts: from treatment to prevention, from hospital to community care, and from analog to digital NHS. While these goals are a step in the right direction, Professor Charlesworth identified critical questions about their implementation and scale.

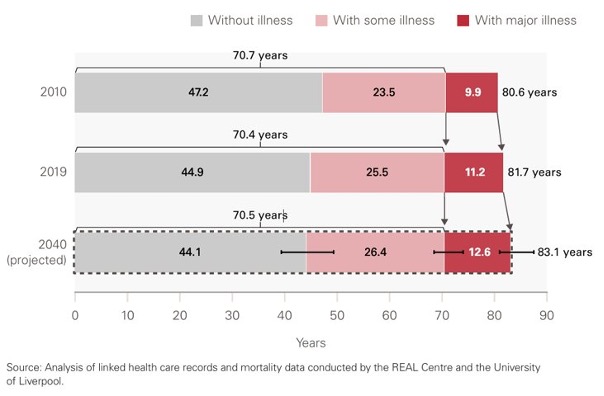

Crucially, Professor Charlesworth honed in on prevention as a core tenet of the Plan, sharing research from the REAL Centre and the University of Liverpool to state that in 2010, on average people lived 9.9 years with major illness – this is projected to rise to people living 12.6 years with major illness in 2040 (see Figure 4). As the UK ages, this means that there is going to be a significantly higher proportion of people living with major illness in the next decade.

Figure 4: Average years of life people spend in different states of ill health, England, 2010, 2019 and projected for 2040

This context makes recent cuts to public health grants—down more than a quarter per head since 2015-16—particularly troubling, especially as drug deaths rise sharply, obesity rates increase, and alcohol-related deaths climb. The proportion of NHS spending devoted to primary care, crucial for managing the chronic conditions projected to grow most rapidly, has fallen from 22% in 2013 to 18% just before the-pandemic. The UK has 15% fewer GPs per thousand population than the OECD average, noted Professor Charlesworth.

However, the impact of better health on NHS spending may be more modest than expected. The OECD estimates that a healthier population would reduce health spending growth by just 0.3% per year. Within the UK, better health only removes 1% from the growth rate of health spending.

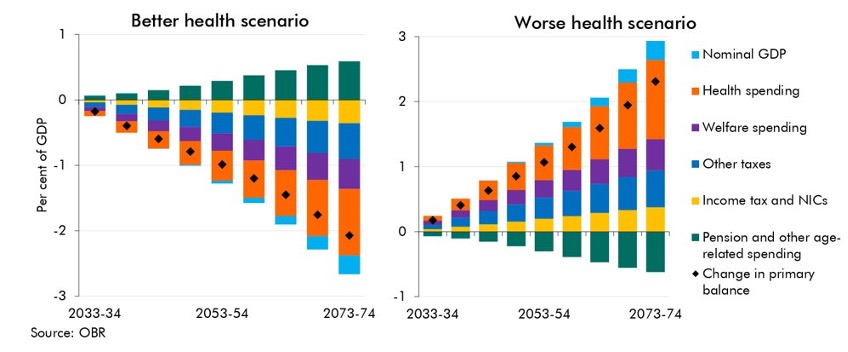

It’s therefore crucial that the health system takes a wider perspective of better health to better inform prevention investments – a healthier population delivers more than just individual health outcomes (see Figure 5). It also contributes to economic growth, averts productivity losses, prevents death, and reduces long-term sickness absence. Overall, public finances are better off as a result of investing in prevention.

Figure 5: Projected impact of population health on public finances

Productivity and the NHS

The next area of focus in the lecture was productivity. Professor Charlesworth emphasized that sustained productivity improvements could make an enormous difference to the NHS. Her analysis showed that meeting the government’s 2% productivity target versus continuing at closer to 1% represents a £20 billion funding difference over the next ten years.

She also looked at the Office of Budget Responsibility’s analyses on how well health spending would do as a share of GDP under different productivity scenarios, finding dramatic differences between a baseline scenario and a higher productivity one.

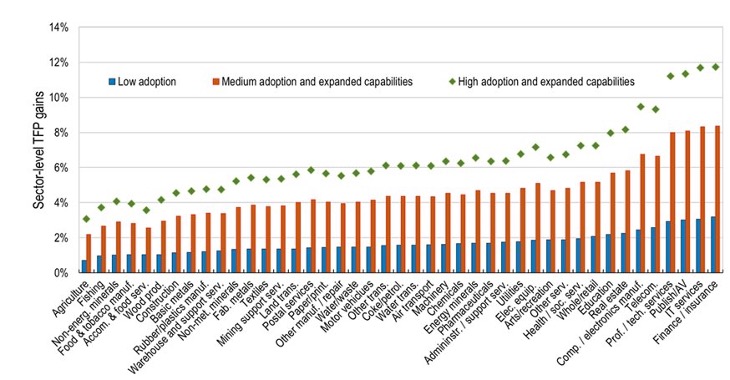

The government’s stated ambitions to focus on digital transformation and artificial intelligence to contribute to its productivity goals is therefore a well-founded proposal. Professor Charlesworth shared OECD research that suggests health and social services have a high potential for total factor productivity gains from AI, with projected cumulative TFP growth ranges of well over 4-6% for healthcare, based on medium to high AI adoption (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: AI-driven productivity gains across sectors (Source: OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers Series)

New technology and innovation may offer us significant long-term opportunities for sustained productivity gain: fundamentally they expand out what we can do. However, she warned that while we may have a more productive health system, we may have even greater pressures on the demand side as we expand what patients expect, and what the NHS can deliver.

The funding question

Professor Charlesworth raised the contentious question of funding in the UK health policy – the balance between public and private spending. She pointed out that currently, despite perceptions of growing privatisation, the share of health spending from out-of-pocket payments and private insurance remains below pre-pandemic and well below levels seen in the late 1990s.

She warned that there is an ever-increasing wedge between cost effectiveness, social value, and affordability. She pointed out that there are current pipelines of high-value therapies with huge upfront costs, delayed value, and uncertainty; although they might work out to be more effective treatments, they challenge system short-term sustainability and long-term realisation of their full social value.

Conclusion

Professor Charlesworth ended her lecture with the assurance that despite the effects of the pandemic and systemic issues within the NHS, all is not lost. A sustainable NHS is possible but needs improved population health, sustained productivity improvements in the NHS and the scale and spread of cost-effective innovation.

She pointed out that the policy directions in the 10 Year Health Plan are largely positive. However, she warned that there remain questions of coherence, capacity and capability. Implementation needs to be revised – many of the preventative measures detailed in the Plan, for example, are still quite small in scale. She also highlighted the gaps in social care across the Plan. Finally, she proposed that the boundary between public and private spending may be something that needs much greater policy focus over the next decade.

The Annual Lecture played a key part of OHE’s thought leadership and commentary around the 10 Year Plan. In addition to the Lecture, we have also published a series of Insights focusing on prevention and sustainability in the 10 Year Plan, with more forthcoming.